The Marcellus Shale is a 575-mile-long stretch of sedimentary rock, most of it deep underground, that settled millions of years ago over the imprint of an ancient sea. It lies beneath much of Appalachia, extending up through western and northern Pennsylvania and a section of western New York. Trapped within the rock are vast stores of natural gas, and because it’s so close to existing gas pipelines and the cities of the East Coast, the Marcellus Shale has long been, for energy companies, an attractive prize—“like discovering an underground deposit of beer directly beneath Yankee Stadium,” the environmentalist Bill McKibben

- print • Summer 2018

- print • Summer 2018

Not since William Steig’s C D B! have I read a book with as many capital letters as Ken Auletta’s Frenemies. Sometimes they appear, without warning, in the middle of names—the “L” in MediaLink, the “M” in VaynerMedia—but mostly they arrive in great alphabet-soup spoonfuls. In the first chapter, we learn that AT&T has dropped WPP, which owns JWT, AKQA, and KBM; later in the book we meet the CEOs of agencies like BBDO and DDB. Auletta sketches out the difference between a creative agency like IPG’s FCB and a media agency like WPP’s MEC; he teaches us that the

- print • Summer 2018

A grim turn of events briefly overtook the barely modulated insanity of our past presidential election season, around the time when the Steve Bannons of the world were declaring war on “the administrative state.” The city of Flint, Michigan, former home of most of the General Motors empire, was found to be in a state of malign neglect usually associated with developing-world kleptocracies like the Sudan or Haiti, as the city’s water supply was shown to be unfit for any human use. Families in the onetime colossus of US automobile manufacturing—which had, not long before, boasted one of the highest

- print • Summer 2018

In the wake of February’s mass shooting in Parkland, Florida, the public American conversation about gun control has been animated by a recurrent theme: the idea of a ban on assault weapons. According to Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi, these guns—most often AR-15-style rifles, civilian versions of the American military’s primary firearm—are “weapons of war” that have no place on “our streets.” But AR-15s are made here in the USA; their manufacturers are subsidized by tax breaks and contracts championed by legislators from both parties. Schumer once called Remington Arms, the oldest American manufacturer of rifles and shotguns, a “proud

- print • Summer 2018

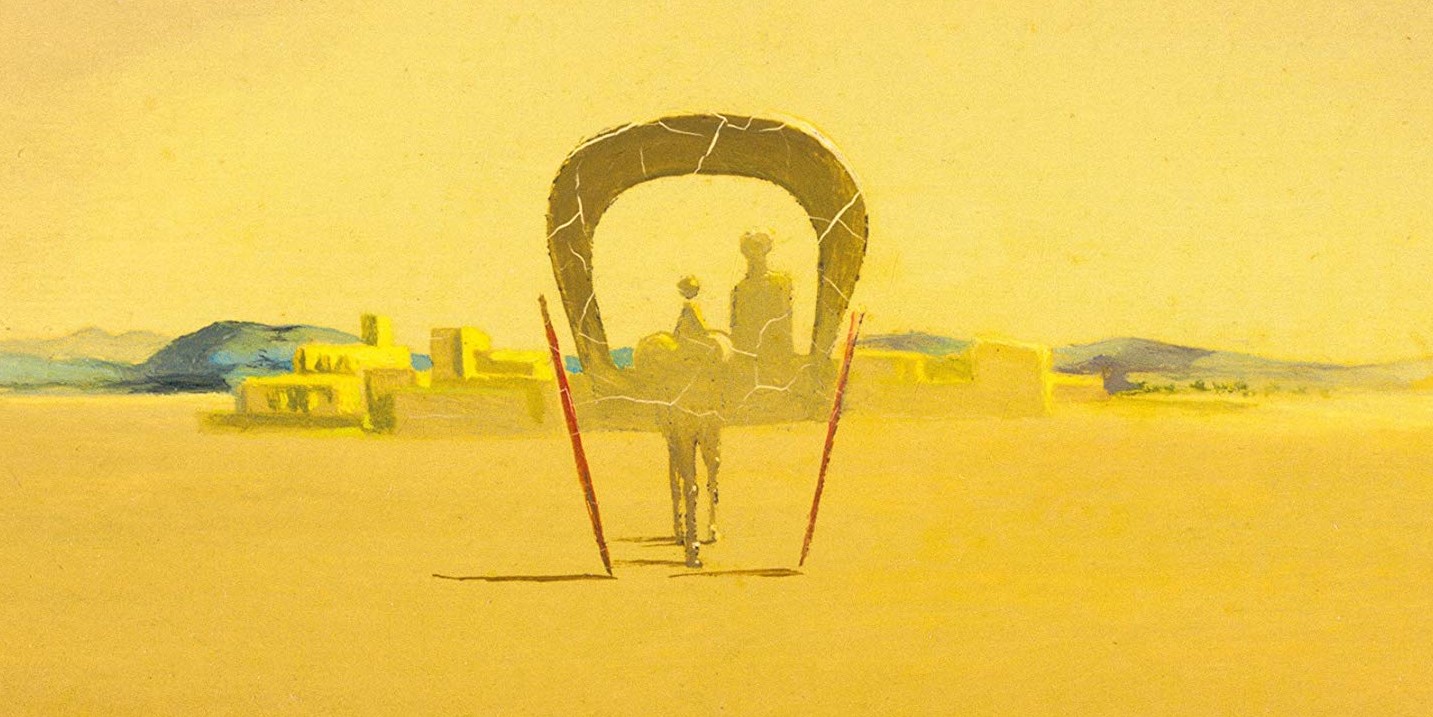

In nineteenth-century America, the word progress signaled limitless expansion and domination: Manifest Destiny was in full force and Americans rushed to exploit the country’s seemingly endless natural resources. In This Radical Land, landscape historian Daegan Miller returns to the era when this idea of progress first took shape. He gives us intriguing counterexamples, writing a history of forgotten communities that advanced a radical vision of what humans’ relationship to the land could be: One defined not by exploitation but by sustainability and interdependence. Surprisingly, it’s a definition that is seemingly in opposition to today’s environmental movement, which largely holds that

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

THE ORIGIN STORY of the 2008 financial crisis is now well known: An American real estate bubble inflated by a risky mortgage business burst. Wall Street got clobbered, spooking lenders, constricting credit, and pushing even low-risk money market funds to register losses. Banks failed; insurers ran out of cash; people—especially minorities and the poor—lost their homes, their jobs, and their money, while the architects of the system suffered few consequences.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

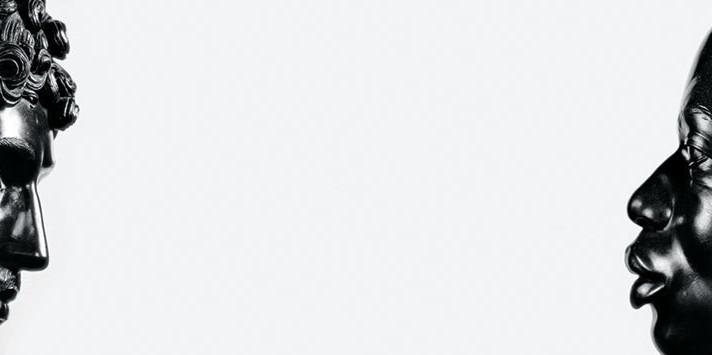

In the period since the 1994 Rwandan genocide, which killed eight hundred thousand people, mostly members of the Tutsi minority, a certain narrative about the country has become inescapable in international news reports. Puny, landlocked Rwanda, it is marveled, has managed to sustain unusually fast economic growth for well over a decade. The journalists often deploy the same tired motif: They are amazed at how the streets of Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, are so clean and orderly.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

Every once in a while the psychoanalyst comes across certain deep beliefs in one of their analysands—a knot in the unconscious that sets a pattern and compels the analysand to act a certain way, again and again. Like the deep state, or the giant web of dark matter structuring the universe, there’s no way to tell exactly when or how it’s at work, or if it’s even there. When this knot emerges in analysis, it is visible only for a moment before ducking back under. The analyst’s job is to draw attention to its importance in shaping behavior—a role that

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

For decades, the forbidding bulk of the 808-page hardcover edition of Witness (1952)—Whittaker Chambers’s fam-ous apologia for his life as a Communist spy, his eventual political apostasy and religious rebirth, and his sensational agon with New Deal golden boy and probable fellow agent Alger Hiss—had resided on the bio-graphy section of our bookshelf, the legacy of a long-ago college paper written by my wife. I mentally filed it away in the category of books I was happy we owned (a valuable Random House first edition) and that I might get around to reading one of these years.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

I’m pretty sure Robert Lipsyte was the first to make the insolent-yet-logical suggestion that the World Series be referred to by a more appropriate name: the North American Baseball Championships for Men. This was back in 1975, when Lipsyte’s SportsWorld: An American Dreamland was first published. It was also the year of perhaps the most riveting of those men’s baseball championships ever, between the Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Red Sox. Superlatives were common in sport that year, which also presented for history’s consideration the epochal third heavyweight championship bout between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, aka the “Thrilla in

- print • Dec/Jan 2019

IN HER 2007 MEMOIR, Flying Close to the Sun, radical leftist Cathy Wilkerson describes feeling perplexed by women’s liberationists in the late 1960s. Wilkerson, who lived on oatmeal in a group home, had renounced her family’s wealth to devote herself to student organizing. Though she agreed with the feminists’ analysis, she couldn’t relate to their unwillingness to make similar sacrifices:

- print • Dec/Jan 2019

The closest thing to a consensus explanation for Trump’s election that has emerged in the wake of November 2016 is the notion that “the Left,” in relying on appeals to “identity politics” rather than to economic class, contributed to the GOP victory by provoking a backlash among white men and workers. In Mark Lilla’s The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics and Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s The Coddling of the American Mind, centrist liberal academics showcased their predilection for battling the Right by punching left. Scornfully arraigning the campus thought police and mobs of online paladins prowling their

- print • Dec/Jan 2019

For the past several decades, the overwhelming majority of Western reporting about Russia has rested on a specific historical narrative about the fall of the Soviet Union. In this story, the USSR collapsed largely from its own economic contradictions. But the heroes were the thousands of ordinary Russians who first supported perestroika and then, in August 1991, turned out in the streets of Moscow to successfully oppose a hard-line Communist coup, precipitating the formal dissolution of the Soviet Union. Though derived from the Cold War school of understanding Soviet citizens as liberal-democrats-in-waiting, this account acquired new influence in the 1990s.

- print • Dec/Jan 2019

It was sometime during the fall of 2010, a dismal mid-term election season, that I found myself waiting and searching for a passionate voice among progressive politicians that could effectively counter what turned out to be a resurgent conservative Republican wave retrieving both houses of Congress that November—and continuing afterward to obstruct any meaningful legislation on behalf of poor and marginalized Americans.

- print • Feb/Mar 2019

Michael Tomasky wants his readers to understand right up front that If We Can Keep It: How the Republic Collapsed and How It Might Be Saved isn’t just another liberal screed provoked by anguish at Donald Trump’s presidency. “Chapter for chapter, most of this book could have appeared just as it now stands” if Hillary Clinton had won the White House, he tells us, and he began mulling the project in the full expectation she was going to do just that. Since Tomasky has written generally favorable books about both her and Bill, it’s a safe guess that she’d have

- print • Feb/Mar 2019

If you’d asked me, fifteen years ago, to picture a group of activists up in arms about illegal immigration, I might’ve imagined a small gathering of eccentrics at some suburban restaurant, passing around xeroxed pamphlets. At least in Texas, where I live, immigration was a marginal concern. Conservative activists here considered gays and lesbians more of a threat than laborers from Mexico. There were two main channels of Republican politics, pro-business and Christian-right, and to be a hard-core nativist was to subscribe to a fusty extremism not really embraced within either one.

- print • Feb/Mar 2019

When I was in seventh and eighth grades, my class’s newfound maturity was channeled into learning about the most difficult moments of the twentieth century in a unit called Facing History. A central focus of the course was on the culpability of ordinary citizens in the worst crimes of human history. During the Holocaust, we learned, ordinary Germans, whether by ignorance or complacency, paved the way to genocide by not speaking up. The resistance to authoritarianism requires constant vigilance by citizens alert to even the tiniest erosions of society’s morals.

- print • Apr/May 2019

At the end of Alice Munro’s short story “Meneseteung,” which reconstructs in painfully intimate detail the life of an all but unknown woman poet in a small Ontario town in the late nineteenth century, Munro’s narrator discovers the poet’s grave, overgrown and forgotten a century later. “I thought that there wasn’t anybody alive in the world but me who would know this, who would make the connection,” she says. “But perhaps this isn’t so. People are curious. A few people are. . . . You see them going around with notebooks, scraping the dirt off gravestones, reading microfilm, just in

- print • Apr/May 2019

Even in a decade not wanting for political weirdness, one of the weirder aspects of the past ten years has been American empire’s guilty conscience with respect to itself. On the campaign trail, both our current and our previous president complained about imperial overreach, about “stupid” wars that cost billions of dollars and weren’t winning the country any new friends. Then, in office, each president kept prosecuting those same wars, editing around the margins without fundamentally changing the scope of the country’s military presence around the world. On both sides of the aisle, our representatives mostly agree that America has

- print • Summer 2019

The lawyer and philosopher Linda Hirshman is a second-wave, no-BS feminist who thinks like a law professor and writes with journalistic chops. She’s also known for writing as if white women’s middle-class experience were universal. It was little wonder that Hirshman dedicated her 2006 manifesto, Get to Work, to a similarly contentious figure, Betty Friedan. In that book, Hirshman laid out a five-point “strategic plan” for “all women to find and be able to pay for the kinds of satisfying lives that a grown up should want to lead.” In short, she rails against being a stay-at-home mom (as she