I CRY EVERY TIME I FINISH SULA. This is not due to any lack of acquaintance with the novel’s tragic ending. Toni Morrison’s second published work of fiction was assigned reading in several courses I took during my studies. I have taught Sula at least once a year for the past ten years. On vacations, I sometimes carry around a dog-eared copy (scarlet-red cover, an illustration of Sula wearing a brimmed hat, flower dress, and fox stole, a “plague of robins” flying overhead). Call it my emotional-support literary fiction.

In fact, I am quite familiar with Morrison’s tale of intense female intimacy and the heartbreak that can accompany the recognition of a love’s real textures, shades, and contours after it is too late. Nel, a young Black girl who comes of age in the light and shadow of her best friend, the enigmatic siren for whom the book is named, only realizes the chasm of her grief years after Sula’s death. The immense pain she experiences requires the context that surrounds it to be properly felt, but when Nel cries “girl, girl, girlgirlgirl” into an unsparing wind, much of the magnitude of their friendship comes into its sharpest focus.

In a novel full of strange triplets and love triangles, this final fractal triptych (girl, girl, girlgirlgirl) typographically reflects the radical melding of subjectivities that readers become privy to over the course of 174 pages. In essence, the deep affection forged between female confidantes will never let one let go of the other. The girls are their own, but they are also one—a gestalt of Black female friendship. Perhaps it is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all, but such knowledge can barely dull the pain of the loss of anyone, let alone she who makes the one complete.

Many of us felt a similar sorrow when Toni Morrison passed away on August 5, 2019. A mind like that, a brilliant mind that made you feel like it was giving you its everything even as it confounded and delighted and frustrated and titillated and comforted and startled, tore a hole in the literary world that will never be filled. When the news circulated, it was like we collectively let out the same mournful wail that escaped Nel’s lips when she finally realized what and whom she was missing: “It was a fine cry—loud and long—but it had no bottom and it had no top, just circles and circles of sorrow.” (Full disclosure: this is the line that drives me to tears.)

Our cumulative grief has produced so much plaintive beauty: eulogies, monuments, memorials, exhibitions, articles, conferences, and now deeply researched and archivally based monographs on the last greatest living American writer are emerging from the pipeline in full force. In 2021, noted Morrison scholar Susan Neal Mayberry released The Critical Life of Toni Morrison, which traces the critical reception of the author’s work throughout her career (a paperback edition came out earlier this year). The summer of 2025 opened with the publication of Dana A. Williams’s hotly anticipated exploration of Morrison’s time editing and acquiring work at Random House, the cleverly titled Toni at Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship. In both of these efforts, the archive of an eminent writer that many find inaccessible is caringly reintroduced to popular audiences, revealing the trials and tribulations that came with being not only a successful Black woman but also, in many ways and in many of the circles she traveled in, the most successful one.

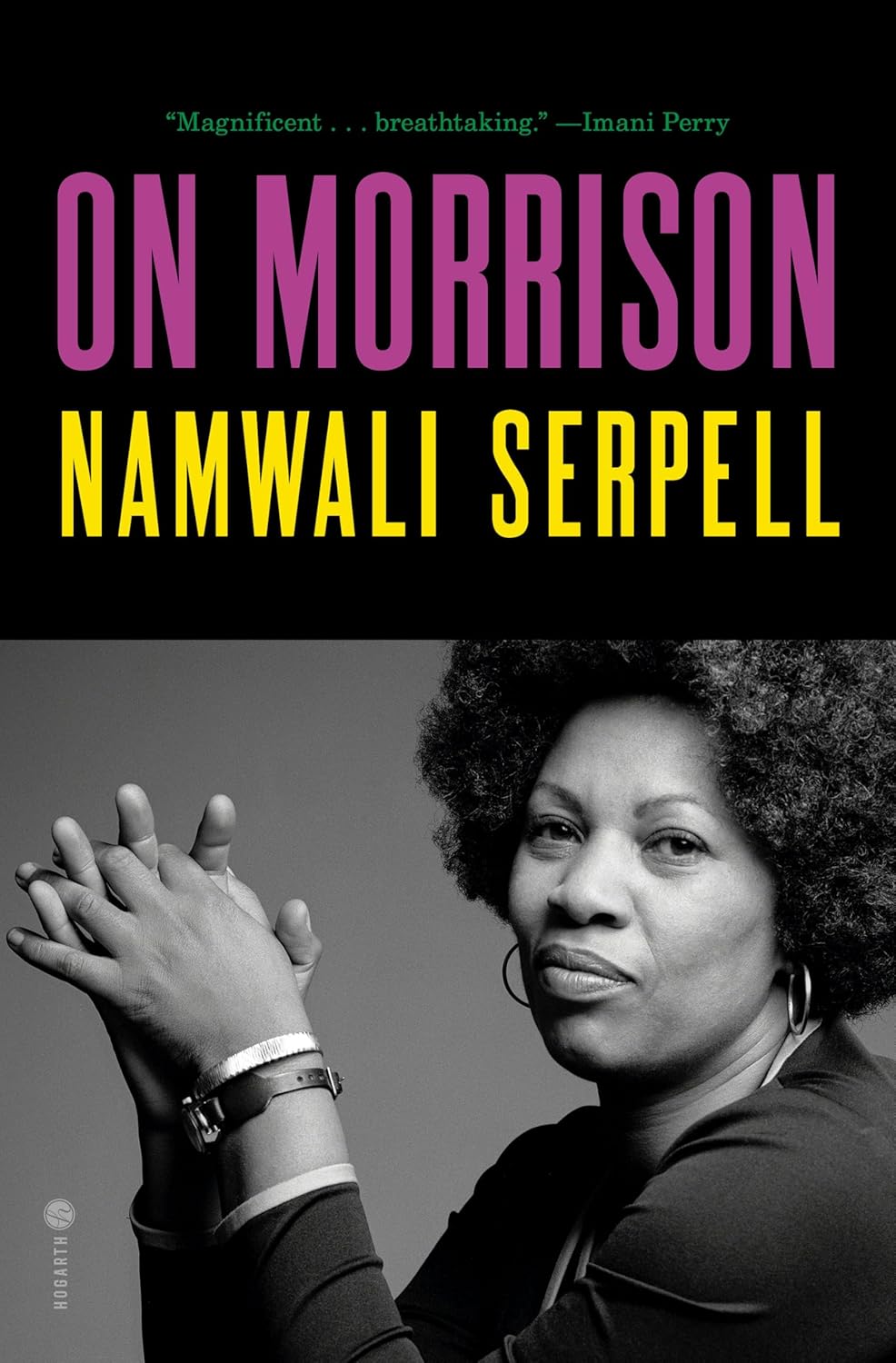

On Morrison, Namwali Serpell’s foray into the expanding field of Morrison scholarship, picks up where these previous monographs left off. Serpell, an award-winning fiction writer and critic and professor of English at Harvard, meticulously pored over archival materials made accessible by the Morrison estate and Princeton University to produce a breathtaking excavation of the inner workings and outer impression of a swaggering Black genius. With this book, Serpell extends Mayberry’s research on Morrison’s critical reception by providing more critical reception of Morrison’s fiction and nonfiction oeuvre. She adds further grist to Williams’s careful exploration of what percolated just below Morrison’s famously steely surface. Altogether, On Morrison homes a novelist-critic’s eye in on a novelist-critic’s body of work and not only considers the beautiful world-building that has enamored publics for decades but does so with attention steeped in the craft of Black virtuosity.

For many reasons, Serpell’s magisterial deep dive into the output of one of the most profound writers of all time should not work. The breadth contained in her subject can petrify even the most seasoned reader; setting out to cover it in its entirety risks resorting to dull platitudes in the face of overwhelming precision. Morrison published eleven novels, one of the most conceptually interesting short stories in the English language, a libretto, several plays, a searing assessment of the place of Blackness in the foundations of American letters, children’s books (some stranger than others), and scores of essays, introductions, and lectures. Serpell’s project, which she describes in part as a labor in “[showing] you how to read Morrison with the seriousness that she deserves,” may sound straightforward but it moves ambitiously.

This study’s twelve chapters mostly concentrate on Morrison’s fiction, but each detours into other public and private writing by Morrison, interviews she sat for, scraps of gossip scattered across her archive, and Serpell’s own work and process, both of which hold some debt to her literary forebear. Though the scope may be broad, On Morrison reads with sharp attunement to the torques of Morrison’s Black aesthetic and the difficulty of living, describing, and elaborating upon the intricacies of Black life.

Serpell begins with difficulty, a charge that has been levied against the seeming inscrutability of much of Morrison’s prose as well as the writer herself. Difficult for whom, however? Serpell recounts one of Morrison’s appearances on The Oprah Winfrey Show, a stop on the promotional tour for her 1998 novel play on the epic form, Paradise. In the transcript for the episode, an undescribed audience member relates their experience of reading Morrison’s narrative of pure Black bloodlines and dueling utopias: “I was lost because I came into—I really wanted to read the book and love it and learn some life lessons; and when I got into it, it was so confusing I questioned the value of a book that is that hard to understand.” Oprah herself reveals the difficulty she had reading Beloved in a charming anecdote in which the former talk show host asks the then greatest living writer if it is “true that sometimes people have to read over your work in order to understand it, to get the full meaning,” to which Morrison incisively replies, “That, my dear, is called reading.”

To notice the difficulty of reading Black literature is to acknowledge the difficulty of rendering Black lives. And to call Black life difficult is not simply to describe the hardship of being Black in an anti-Black world. Complexity, ingenuity, beauty—all are contained within Blackness and are difficult if not impossible to fully comprehend at the time of their witnessing. To read Morrison is often to feel wiped out by the most elegant tidal wave only to get back on your surfboard and swim headfirst into the next one. Or, as Serpell suggests in how she chooses to bring the legacy of Morrison with her into the future: “I will remember Morrison for her masterful difficulty and her superb wit, for her inscrutable yet perfect metaphors, for what her unaccountable rushes of imagination carved into our ground, for what spills into place and what floods in me whenever I read her.”

Much of the shrewdness in Morrison’s terse and, as Serpell notes, shady response to Winfrey lies within the unstated premise that Black literature is not just worth reading but that much of it demands rereading. It is only through the act of rereading that close reading as a method of interpretation and analysis really punctures the surface of literature. Serpell recounts how many elements of Morrison’s work specifically and Black literature generally have remained at least partially shrouded to her over the course of her life. Parsing that which resists parsing constitutes much of the fun of learning and struggling with Morrison but, as Serpell describes in her approach to reading, teaching, and sifting through any Black literature: “Whenever I read or teach or write or think about black books, I feel daunted. What kind of difficult do I want to be? Do I insist on the ingenuity and complexity of black aesthetics? Can I simultaneously refuse condescension and commit to solidarity? Is there a way to defend black culture without sounding sentimental or aggrieved? How do I acknowledge that while black suffering may be the subject, black art is the form—and the point?”

While the answers to these questions may come via close attention to detail in both initial and subsequent readings of a text, some of Serpell’s most interesting interpretations refuse resolution and lean into ambiguity. Sula Mae Peace’s name may derive from “Shulamit, the name of Solomon’s beloved in the Song of Songs, the woman whose lips are as sweet as the honeycomb” or “Salome—either the temptress who danced for King Herod and demanded the head of John the Baptist at the behest of her fiery mother, or the female disciple who witnessed Christ’s crucifixion.” Disentangling these names is unnecessary, however, because both words are derived from “shalom,” a Hebrew word meaning peace, so, as Serpell observes, “Sula Mae Peace is also Peace Peace, an analeptic doubling that jars her loose from herself.” Even the reason for the indefinite article in the title of Morrison’s ninth novelis a cause for conjecture: “I can’t help but wonder if she landed on the slightly off-kilter title A Mercy not only because its indefinite article defamiliarizes and secularizes the concept of mercy, but also because it forms a near-anagram of the word America. When the novel names itself at the end of its storyline, we see how Morrison’s anagrammatic late style allows her to reprise and write back to her masterwork of American historical fiction, Beloved.”

Late works “often stymie closure and refuse clarity,” as Serpell, informed by the literary critic Edward Said’s work on “late style,” suggests. But what she makes clear is that Morrison’s style has always been late in that way. This is not a reference to the fact that The Bluest Eye was published when Morrison was almost forty years old, a tidbit about the writer’s life that has circulated widely after her death as evidence that you are always young enough to start over. Rather, Morrison’s dexterous command of language always seduced readers with a devastating neatness that invites them in from the cold but asks them to find the key to the door somewhere else on the property. Serpell provides something of a map with the caveat that she is still searching for the key, too.

Serpell’s reading of Beloved, Morrison’s most well-known novel and, in many ways, her most difficult, exemplifies the carefully speculative approach she takes to work she most intimately knows. The chapter begins with two deceptively simple questions: “Why is Beloved a ghost story? . . . Why would Morrison use a haunted house story—with its campy, Halloweeny vibe—to depict a subject as devastating as American slavery?” These questions, which first arose for her while teaching the novel in graduate school, continue to (excuse me for a moment here) haunt her.

So much about slavery is frightening—the threat and actualization of stolen children and family members, the alienating brutality, what scholar of slavery Orlando Patterson calls the “social death” of being human with none of the legal or social protections that come with being under the jurisdiction of a state. For Serpell, it is not merely that the genre of the ghost story cannot properly capture the horrors of the experiences of the enslaved. In fact, her argument follows the same line as a quote she includes from William Wells Brown, the nineteenth-century Black abolitionist and writer who has been credited with publishing the first African American novel, “Slavery has never been represented; Slavery never can be represented.” This presents an obvious problem for fiction meant to depict slavery, even that which is written a century after its legal eradication. How can language come close to approximating that which violently resists capture?

For Serpell, in the case of Beloved, these terrors must be approached orthogonally through an affective vehicle that many cannot fathom in this context: love. What may seem like a novel entry point into what might be unrepresentable makes sense when imagining the enslaved as the humans that they are. Language imposed untold cruelty onto the enslaved via decrees of the law, reports of scientific racism, the caricatures of Black people in literature that Morrison elsewhere locates as central to the underpinnings of American culture. But love, which repels full representation just as strongly as slavery does, can haunt much in the same way slavery has as well.

How else other than through love’s prism should we read the act that sets the action of Beloved in motion: the murder of a child by her enslaved mother? Serpell presents a few options that repeatedly return to genre. Subsequent chapters in Morrison’s novel in which mother, living daughter, and ghost daughter (or embodiment of the sixty million and more enslaved persons who were murdered or “a slave ship survivor inhabited or possessed by the spirit of Sethe’s dead baby girl” or another wayward apparition altogether or or or . . . ) keep these girls and women separate at just the moment in which the embodied spirit named Beloved tries to become one with she who might be her mother.

As Serpell notes, each of these chapters begins with words of self-possession. “Beloved, she my daughter. She mine.” “Beloved is my sister. I swallowed her blood right along with my mother’s milk.” “I am Beloved and she is mine.” This invocation of ipseity, a word Serpell uses in her chapter on Sula that she usefully defines as “the unique quality of self,” pushes the threat of the loss of selfhood that slavery demands of the enslaved into the promise of community that slavery meant to deny. And it is the genre of the ghost story that helps usher in this radical act of self-possession in communion with others, according to Serpell: “Morrison counters the will to join with an ethos of the adjoining. She opens up the claustrophobic ghost story by making it communal in form, stretching it to accommodate the black aesthetic mode that she called ‘the presence of an ancestor,’ which is one of the ways she felt her writing was always ‘about the village or the community.’”

This particular kind of analysis, which brings together genre criticism, elaboration upon literary technique, Black studies, and a keen emphasis on the entanglement of history and aesthetics can be found all over On Morrison. In this way, there is something for everyone: seasoned scholars of Black literature, aspiring fiction writers, and casual readers of Toni Morrison will all delight in Serpell’s prose style, which can flash between breezy rigor, delicious gossip, and curious appreciation in the span of a few pages. Serpell adores Morrison, and that love is infectious, even for those of us who knew and loved her before we cracked Serpell’s work open.

On Morrison ends with a meditation on Morrison and monuments, raising the question for readers if this should be counted as simply more commemoration. It is not as if Morrison does not deserve memorialization or that she would ever spurn it. Serpell recounts the writer’s keynote address for a symposium occasioned by the dedication of a building named after her at Princeton University: “‘I am not humbled,’ she said, with typical braggadocio and to much applause. Then she joked about the mouthfeel of ‘Morrison Hall’: ‘Sounds good, doesn’t it? The more I say it or murmur it, the more natural and even inevitable it seems.’”

If Serpell’s resplendent readings of the only Black female recipient of a Nobel Prize for Literature are a memorial, they are quite the fitting one. This fresh and smart volume of criticism on Morrison’s work pierces with a playfulness that can only come from intimate knowledge and diligent intent. She utilizes the heights of her skill as a novelist and a critic to push public, popular, and scholarly knowledge substantially forward. Whoever eventually writes On Serpell will have a difficult task ahead of them.

Omari Weekes is an assistant professor of English at Queens College, CUNY.