WHEN A WRITER undertakes a tribute to a pop star, where does the fan end and the critic begin? Can (or should) those roles be separated?

In Stephanie Burt’s Taylor’s Version: The Poetic and Musical Genius of Taylor Swift, it’s clear that the author is writing about one of the great, defining loves of her life. The earnestness of her emotion is palpable on every page—in her passionate assessments of the subject’s work, in her sensitive chronicling of how the singer has navigated the spotlight, and in a few stray indications that Burt has spent some time actively worrying about her idol’s well-being (“who will take care of Taylor?” she wonders at one point). As much as anything else, pop music has the power to change lives and shape identities, so it’s no surprise that some people feel compelled to write books about it. But at the heart of Taylor’s Version—and perhaps any project of this kind—is the sense that such love requires justification, evidence that it runs deeper than blind hero worship. Through the act of methodical analysis and the occasional consideration of divergent perspectives, the writer implicitly distances herself from the cultishness of today’s social-media-fueled standom, hoping to emerge as a levelheaded explicator of an appropriately weighty subject.

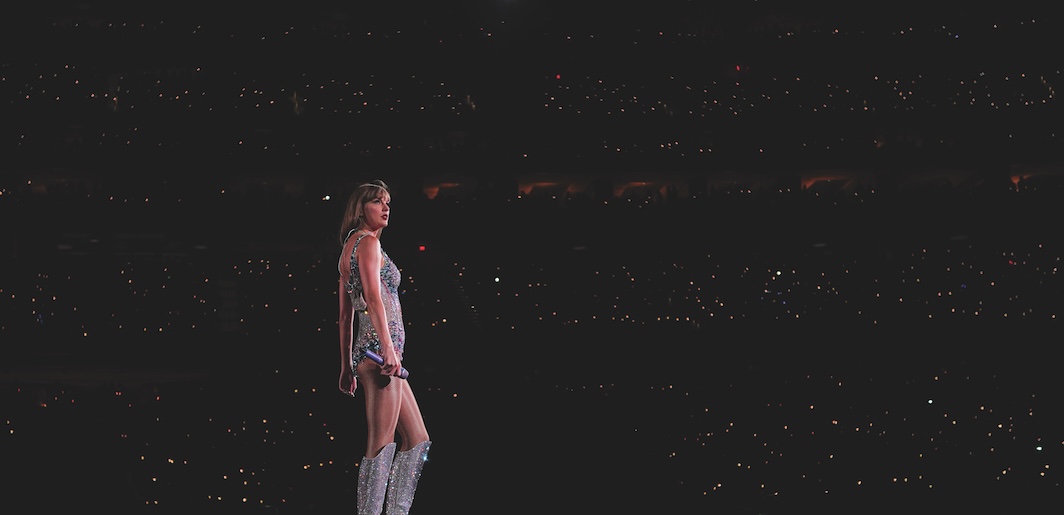

Taylor’s Version is the culmination of an ongoing academic endeavor that began in 2023, when Burt, an acclaimed poet and an English professor at Harvard, first devised a course on Swift. Students clamored to register, and news media from around the world reported on the class, amplifying the Ivy League canonization of a singer-songwriter whose cultural dominance (what pop fans like to call a star’s “imperial phase”) has now lasted nearly two decades and shows no signs of waning. The book lands in the wake of Swift’s record-breaking Eras Tour, which thundered across five continents, grossed over two billion dollars, and cemented her as the most successful pop star in the world—an anomaly at a time when even artists with major-label support and sizable followings struggle to turn a profit off their music.

Taking its cues from this marathon of career-spanning shows, Taylor’s Version covers the singer’s discography album by album. Burt’s chronological approach isn’t as fun as the free-associative, go-where-I-please method of Rolling Stone critic Rob Sheffield’s 2024 Swift study, Heartbreak Is the National Anthem, but it registers as perfectly sensible: how else to fully capture the drama of the subject’s metamorphosis, which has taken her from a privileged childhood in West Reading, Pennsylvania, to her early triumphs as a country-music wunderkind to global, monocultural fame as a genre shape-shifter absorbing the influences of trip-hop, dance, folk, hyperpop, and indie rock? And how else to take in the scope of an oeuvre that is fast approaching three hundred songs?

Burt’s wide range of academic interests—extending from the history of English poetry to science fiction and graphic novels—has trained her in addressing different audiences, making her remarkably attuned to what will interest both hardcore fans and readers (like me) who have managed to stay agnostic about this most ubiquitous of artists. Having fallen under the spell of my own idols, I’m sympathetic to anyone trying to grapple with the very particular kind of amour fou that bonds musicians to their followers. And over the years I have found enough to enjoy in the singer’s work—particularly her 2017 minor hit “Delicate” and her 2019 smash “Cruel Summer,” two of contemporary pop’s most vivid evocations of anxiety-ridden seduction—to be interested in taking a guided tour of her universe.

Burt is on her surest footing when appreciating the details that make Swift a distinctive songwriter. For instance, “Hey Stephen”—released in 2008, when Swift was nineteen years old—might strike me as juvenilia, but Burt makes a compelling case for its sophisticated use of “liquid consonants,” an “irregular bass line,” and a metanarrative that shows the artist in conscious control of the process of composition. Burt has a good ear for old-fashioned Nashville songcraft, but she is just as astute when explaining the singer’s approach to track-and-hook composition, a standard contemporary-pop practice in which the creation of melody and lyrics is guided by a producer’s preexisting beat. In the relentless repetition of the title phrase in 2014’s “Out of the Woods”—one of several outstanding tracks on 1989, the album that definitively marked Swift’s departure from the country-music establishment—Burt hears a brilliant conjuring of romantic angst. You can sense the author’s determination to get to the bottom of what makes this potentially mind-numbing device so riveting, as she slips into the skin of the song to uncover its vertiginous logic: “No, we’re not out of the woods, and we will not be out of the woods until I stop feeling compelled to ask myself, or ask you, again and again, whether we might be out of the woods.”

Taylor’s Version is packed with such fine-grained insights, which typically fuse Burt’s effortless command of prosodic technique (she revels in Swift’s arsenal of literary devices, including adianoeta, syllepsis, and zeugma) with an intuitive feel for the music’s emotional stakes. The latter is rooted in her encyclopedic knowledge of the biographical lore surrounding Swift’s persona. As Burt makes clear, Swift’s life and art are much too closely linked to be disentangled—after all, “Taylor’s genius involves turning the accoutrements of fame, the troubles that come with having paparazzi follow you everywhere, into relatable, empathetic dilemmas.”

It’s fitting, then, that the best part of the book is a seven-page stretch on “All Too Well,” a breathtaking ballad that sits comfortably next to Fleetwood Mac’s “Silver Springs” in the canon of post-break-up catharses widely understood to involve real-life celebrity protagonists. Considered Swift’s signature achievement by many critics (as well as Burt’s own students, according to a poll the professor once conducted in her class), the song has long been rumored to be about Jake Gyllenhaal, whom Swift dated for a few months in 2010 and 2011. A decade later, “All Too Well” was rereleased in a ten-minute version that underscores Swift’s talent for framing everyday heartaches and resentments (what Stevie Wonder called “ordinary pain”) in epic terms.

The song unlocks something in Burt, who pulls out all the stops to demonstrate how a great piece of music—even one that mostly adheres to tried-and-true pop conventions—grows in complexity the harder and longer you listen. Not only does she make a convincing argument for the richness and precision of the songwriting—its disquieting off-rhymes, its haunted sense of time, its echoes of Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain” and Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused—she also catches unacquainted listeners up on the relevant backstory with a light, compassionate touch, and effectively compares the song to popular elegiac works by John Keats and Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

It’s a beautiful passage of criticism, one that successfully transfers the pain and grandeur of Swift’s masterpiece to the page. But not everything Burt chooses to cover warrants such thorough examination, contrary to the critic’s preposterous claim that “every sound and word in almost every Taylor song not only solicits attention but rewards it.” As Burt moves relentlessly from one song to another, she is hard-pressed to avoid repeating the same points, leaving us to wonder if the book might have benefited from a more tightly curated selection of objects for study. Burt also stumbles when she ventures away from the particularities of these texts, seeking to pin down the Swift persona, often in an effort to glean some deeper cultural meaning from it. This impulse is most apparent in Burt’s frequently reiterated thesis, which posits that the singer’s genius lies in her ability to “stay both aspirational and relatable.” Try as she might to define these adjectives, they remain hopelessly vague, and their application to such a broad swath of listeners is often presumptuous. Why, for instance, would I relate to Swift’s drive toward hyper-productivity if I’m not similarly inclined? Why does Burt think that I would aspire to have Swift’s glamorous love life if I don’t share the singer’s taste in ultra-famous men or her apparent capacity for highly public romance?

The question of how relatable a white billionaire like Swift could be (and why it should be so easy for Burt to assume that anyone would naturally covet the singer’s existence) leads us to the subject of racial privilege, which the author clumsily explores in her chapter on Swift’s 2017 album Reputation. Despite some statements she has made against Donald Trump’s bigotry, Swift has long been politically ambiguous, in a way that strikes her detractors as all too convenient and downright irresponsible. Many have noted that, while fellow pop stars like Olivia Rodrigo have rebuked the Trump administration’s use of their music or taken public stances against Israel’s violence in Gaza, Swift has remained silent. In the years since her infamous feud with Kanye West positioned her as an avatar of white-woman victimhood, white supremacists have embraced her as an “Aryan goddess,” while some listeners of color have come to see her as white mediocrity personified (or, worse, a “Nazi Barbie,” to borrow a phrase from essayist Vanessa Angélica Villarreal).

Burt leverages Reputation’s affinities to hip-hop and R&B as a way to talk about Swift’s racial coding, and you can feel her discomfort in every rhetorical move she attempts. She certainly isn’t wrong to raise the perennial question of cultural appropriation. But her analysis lacks sufficient acknowledgment of the fact that Black music, far from being an exotic source of fascination, is an omnipresent and defining force in mainstream American culture. This makes Swift’s references to it less provocative or exceptional than Burt thinks they are. The desire to extract a worthwhile lesson from Swift’s use of Black styles leads Burt to conclude that the album is some sort of brave repudiation of the singer’s “inner, insistently harmless, agreeable, all-too-white child”—a rebellion the author thinks “might prompt white people to think about whiteness.”

It’s here that Burt’s fan loyalties dull her critical faculties. She identifies a tired old trope—white people’s reliance on Black aesthetics to facilitate their own spiritual education—and tries to pass it off as a legitimate path to self-improvement.

A similar urge for political redemption fuels Maggie Nelson’s The Slicks: On Sylvia Plath and Taylor Swift, which contends that the key criticisms put forth by Swift’s naysayers—that the apparently autobiographical nature of her songs is narcissistic, that she releases too much mediocre music, and that her wealth and ambition render her morally suspect—are rooted in a long tradition of putting powerful women in their place. To those naive enough to “grouse that Swift’s artistry is tainted by its being the engine of a billion-dollar industry,” all she has to say is “welcome to the world of pop music; it ain’t poetry.” Nelson views the “profusion,” “pour,” and “spill” of Swift’s art not as a strategy for market dominance or the result of capitalism’s ceaseless demand for product, but as a feminist achievement—and, like the work of Plath in her time, an antidote to what Anne Carson has identified as the ancient Greek virtue of sophrosyne, which upholds masculine ideals of “prudence, soundness of mind, moderation, temperance, self-control.” Swift may not intend to “subvert femininity,” but in Nelson’s view, the singer’s voluminous output has freed her young female fans from the roles of “maiden, wife, mother, and so on,” teaching them that life can be “literally what your art makes of it.”

Unlike the celebratory Taylor’s Version,this slim book-length essay is essentially defensive in its aim and tone. But the effect is confusing, partly because Nelson seldom quotes or cites the dismissive commentary that Swift has been subjected to. One might emerge from the book with the impression that Swift has a low approval rating among our leading arbiters of taste, when in reality she has won more Album of the Year trophies at the Grammy Awards than any other artist in history and regularly appears on critics’ best-of lists. She is also exhaustively covered in the press, as exemplified by the fact that USA Today has hired its own staff writer dedicated to the Swift beat, and the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism reported this year that many reviewers who have had negative assessments of her work have found themselves the target of harassment and doxing by her most rabid fans. Because Nelson offers little insight into what makes Swift a great musician, we are left to understand the singer’s legacy merely as one of power being acquired, exercised, and sustained for its own sake. Nelson writes about this with a sense of wonder, as though ambition were an inherently admirable quality.

Burt’s and Nelson’s books vary in their strategies, preoccupations, and persuasiveness, but in the moments where they fail, they do so in the same way: by prioritizing the writer’s eagerness to free Swift from the status of “bad object.” It is not enough for the authors to declare their love for the music; they want us to know that there is something righteous and life-affirming in their choice of idol—because Swift “can bring people together,” and because Swifties are a “uniquely expansive” and “uniquely welcoming” fanbase (in Burt’s words); or because her songs stem from a “devotion to living, making, management, and survival” (according to Nelson). There must be a way to convey the sublimity of music without making such extravagant claims for its nobility.

The widely shared experience of loving pop stars means that many of us know what it’s like to be in thrall to powerful people we’ll never get to meet—and to even view them, sometimes against our better judgment, as what Burt calls (borrowing a phrase from the poet Allen Grossman) “hermeneutic friends.” There’s no denying how intensely personal the relationship between fans and artists can be: as we follow our favorite singers through the decades, flooding our ears with the sound of their voices, using their work to cope with challenging moments in our lives, and creating indelible memories around them, we start to see them as integral to who we are—and perhaps wonder if others’ appreciation or rejection of them might reveal something about how we are perceived. Writing a book about a beloved pop star is a way of formalizing that connection and trying to get the world to take it seriously. But part of the critic’s responsibility is to discern what is real and what is illusory in such an attachment, and to refrain from assisting the star in selling an individual quest for wealth, fame, and perpetual validation as a wholesome creative act that empowers us all.

Andrew Chan is a writer living in New York.